“In the depth of winter, I finally learned that within me there lay an invincible summer.” -Albert Camus

Inside every person, there is always something — a restless pulse, a secret ferment — yearning to break free. Sometimes it comes out as a craving, a boiling urge, a writhing impatience, always searching for a way. I have seen people release it in a hundred ways: in the easy laughter of a social gathering, in the sharp sting of an insult, in the catharsis of a few slaps, and, darker still, in the cold violence of murder or the raging storms of genocide. Expression, I learned early, can be poison or medicine.

For the introvert, the turmoil stays inside. And when that introvert is also highly sensitive, the inner weight can pull them into depression — sometimes deeper, toward the edge of self-destruction. But there are other ways. Literature, art — these are the patient and luminous mediums that let you pour yourself out without spilling into harm. A single stroke of a brush can erase an old pain and leave behind a new beginning. Twenty-four syllables in a couplet can awaken something buried for years. One sentence from a wise mind can turn the wheel of your life. A scene performed — or even just watched — can melt the long-cooled lava inside you.

Michelangelo once said, “The sculpture is already complete within the marble block, before I start my work. It is already there, I just have to chisel away the superfluous material.” I have come to believe the same about the self: we are all statues waiting to be freed from the rock.

I grew up in a farming belt where life was simple, the air thick with harvest dust — and my own inner fields were busy growing something unseen. Slowly, almost shyly, it began to search for a voice. First, it found song. From song it moved to song-drama, then to play after play. Later came poetry, then prose, then children’s stories. And alongside all of it, research and criticism wove themselves into the fabric of my life.

But the soil around me was dry when it came to books. Reading and writing were not common in my village or in my family. One truth I discovered over the years is that, in our culture, the bond between a father and his elder brother — the taaya — and the children is often strangely distant. They are close in blood and age, but tradition builds a wall called the ‘generation gap.’ The younger paternal uncle — the chacha — is often the bridge that lets the new generation cross over.

In those days, families were large, and it wasn’t unusual for a father to have half a dozen siblings. The children of the eldest brother were sometimes the same age as the youngest chacha or bua. That closeness made the sharing of joys and sorrows more natural, and the younger uncles often became role models. In my own life, my chacha was exactly that.

No one in my home, our village, or among nearby relatives had much formal education. My chacha was illiterate, but he had begun, bit by bit, to learn Gurmukhi letters. Secretly, he loved reading qisse — long folk romances. In those days, this habit was seen as a little wayward. He would bring home paper-sized, coverless stories like Dahood Badshah, Jaani Chor, Sucha Soorma, Jiuna Maur. He would fold and twist them, tuck them in a clothe he worn around his waist., and when no one was looking, read them — and at night, slip them under the bedding.

I would find them there, under the bedding, and sing them out loud with the same fire in my voice as his. By the time I was in third or fourth grade, I had learned Gurmukhi not from a classroom but from the rhythm and music of those lines. In Haryana, Punjabi was taught to us only from the seventh grade — but by then, the seeds were already planted.

Those seeds grew into songs and song-dramas, into plays and poems. They brought me here, to this life, where I still carry that same yearning inside — the same “I and I” — forever searching for a way out, and finding it in words.

I was born in Rojhanwali, a small village in the Fatehabad district of Haryana. Rojhanwali is a place that sits right on the edge of two worlds — the last village of Haryana if you’re coming from Punjab, and the first one you step into if you’re crossing over from Mansa district in Punjab. Both districts, Fatehabad and Mansa, share the same fate — labelled as “backward,” a word that stings more when you have lived it.

But Rojhanwali carries another peculiarity: though it stands on Haryana’s soil, every soul here speaks Punjabi and follows the Sikh way of life. From my earliest memories, there was this quiet ache inside me — we were Punjabis through and through, yet we didn’t belong to Punjab. I grew up with that longing, a strange pull toward a place just across the border, so close I could almost feel it in the air.

My schooling was all in Haryana. I only began to study Punjabi formally in the 7th grade. Until then, it was the language of my tongue, my lullabies, my prayers — but never my textbooks. And only someone who has lived that peculiar gap — speaking pure Punjabi yet never reading or writing it until adolescence — can understand the flood of affection and pride that rushes in when you finally meet your language on the written page. That joy is part of my village’s story, and part of mine.

My father, Sardar Jang Singh, and my mother, Sardarni Balbir Kaur, were humble farmers. Ours was a home where no one had ever been to college — or even passed matriculation. Not my family, not my relatives, not my neighbours. I was the first to break that ground: the first to pass matric, the first to earn a B.A., the first to complete an M.A., and, eventually, the first to land a job. In some ways, my journey was not just mine — it was the beginning of a new chapter for my entire village.

I was born in a house with few resources, in fields where survival was a daily task, and in a society where opportunities were scarce. I grew up in a cultural climate that was not quite my own, in the economic reality of small farming, and in an educational landscape that had little to offer. But it was in those very conditions — resource-less, broken, and unyielding — that I learned what it meant to hunger for something more, and to keep walking toward it.

I never set out to be a writer. In fact, the thought had never even brushed against my mind in any conscious way. I was born into a place where words were used for work, not for literature — where there were no books in the house, no poets in the streets, no circle of friends who might lead me toward a literary path. My village had no such air, and neither did my home. If I found myself on this road at all, it was either pure chance or some stubborn ember of passion that refused to die out.

It began — as so many turning points do — in the most unassuming way. There was a college in Ratia where a friend of mine studied. They held an annual festival, and that year he asked me to help prepare something. I didn’t know much, but I cobbled together a couple of choreographies. Then, almost on a whim, I wrote a short du-gāṇā — a Duet Song — about the life of an addict, framed as a conversation between a husband and his wife. Du-gāṇā singing was popular then, so I gave the piece a purpose, a message. Du-gāṇā is that form of Punjab’s song tradition in which each verse is sung alternately by a man and a woman in a dramatic style. It usually includes sharp questions and answers on some subject, playful humor, the mutual dialogue of two lovers, and also the presentation of some custom or ritual from Punjabi culture.

When we performed it, the response was electric. People didn’t just listen — they leaned forward, they felt it. Something in that applause told me the piece could be more. So I expanded it. Instead of one addict, there were now three. Alongside the wife, I brought in a son and a daughter. Six characters in all. We called it Eh Jang Kaun Laṛe — “Who Will Fight This War?” — a play against the scourge of drug abuse. And here’s the curious part: every line, every exchange, was in song. The title song of this play was as follows :

Listen, tomorrow’s new inheritors,

Our wounds are still fresh.

From this demon of intoxicants,

Tell me, how many lives have perished?

It devoured many living corpses,

And buried desires deep in graves.

It swallowed even the burning suns,

How will tomorrow’s dawn ever rise?

We have fought countless battles —

But tell me, who will fight this war?

At the time, I didn’t know such a form existed anywhere in the world. Many years later, when I went to do my PhD under Dr. Satish Kumar Verma, he suggested I research opera. I remember asking, honestly, “Sir, what is opera? Please explain it to me first.” He smiled and said, “A play performed in song is called an opera.”

It was only then — six or seven years after that college festival — that I realized the little play I had written in a dusty village, without knowing the name for what I was doing, had in fact been my first opera. And that, without plan or prediction, was how my journey as a playwright began.

The real journey began after that — one that would keep me rooted in Mansa for almost two decades. I made that dusty town my headquarters, a kind of anchor, while my feet kept moving across the Malwa region, carrying theatre wherever I went. I worked under the banner of my own group, “Shaheed Bhagat Singh Kala Kendra, Boha.”

There was a time when this land felt utterly barren — barren not of crops or people, but of art. From the standpoint of creativity, it was an empty field where nothing seemed to grow. Yet I could not accept that silence. With the encouragement and help of my colleagues, my fellow teachers, I began to work this soil in another way. Together, we tilled it, softened it, and dared to sow the smallest seeds of art.

At first, there was nothing but patience. Then, slowly, tender shoots began to appear. Over the years, those fragile shoots grew into blossoms of many colors, spreading fragrance into every corner of this dusty Malwa region. What once seemed a desert of art is now a flourishing garden, alive with the voices, colors, and rhythms of creativity.

It all began with a modest effort: the founding of Shaheed Bhagat Singh Kala Manch, Punjab. That was back in 1996. Since then, the Manch has carried forward the work of sowing and blooming, season after season. We have held twenty-eight great “art festivals” — each one a new harvest of talent and expression. And just last year, in 2024, at Mansa, we celebrated the twenty-eighth Art and Book Fair. From barren soil to a living, breathing orchard of creativity — that has been the journey.

In those days, Boha (District Mansa), this region of Punjab was as barren in theatre as it was in other arts. This was the tail-end of Punjab, nudging the border of Haryana, and no theatrical current flowed in from either side. If theatre was to happen here, it would have to be born here.

I began by pulling my students into plays for competitions — coaxing, persuading, sometimes dragging them onto the stage. From there, I trained them to stand on their own feet as independent actors. We performed not for a season or two, but for nearly twenty years. We had no formal training in direction or acting, but we learned the only way we knew — by doing, by failing, by doing again. For us, theatre here was never just a hobby. It was a duty, a responsibility to the soil we stood on, and we carried it out with whatever strength we had.

Over time, my troupe of eager students transformed into a company of teachers, each carrying the torch forward. We travelled far beyond Mansa — to Jalandhar, Chandigarh, Delhi’s Little Theatre, and even the grand Kamani Theatre. In 2015, I moved from Mansa to Patiala, and the rhythm of my life shifted. Theatre took a quieter place in my days as literary work called to me more insistently. Now, my old comrade, Surinder Sagar, steers the group’s performances, while I spend most of my hours shaping words into plays.

Through it all, I have learned something about life and literature. Nothing in literature is a mirror image of life — but much of it is drawn from life’s vast and messy storehouse. Life is immense, full of layers and contradictions, of fleeting joys and enduring sorrows. Every day it offers up countless events, big and small, good and bad. A writer’s task is to choose, to distill, to arrange them in a form that feels true without being exact.

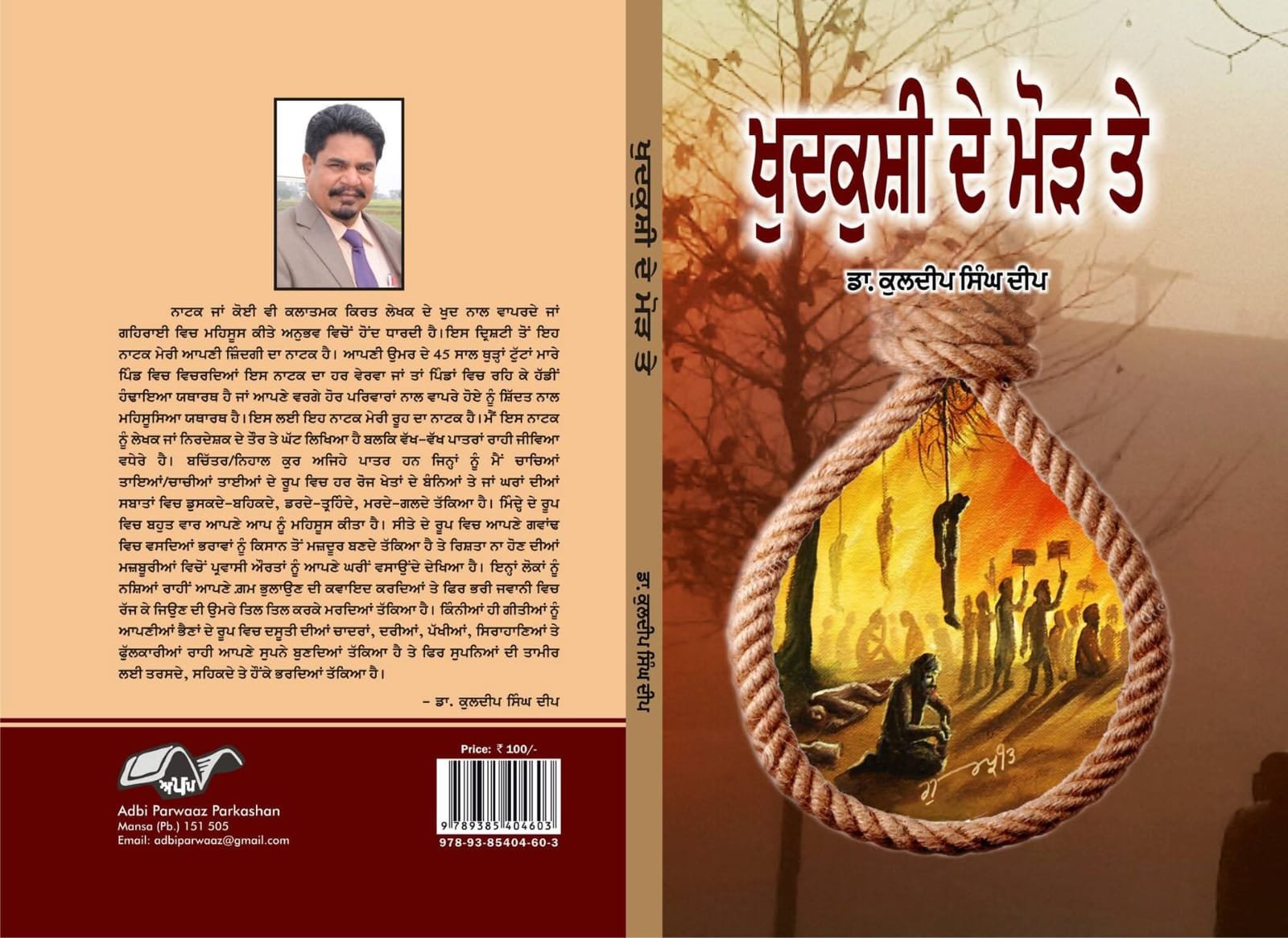

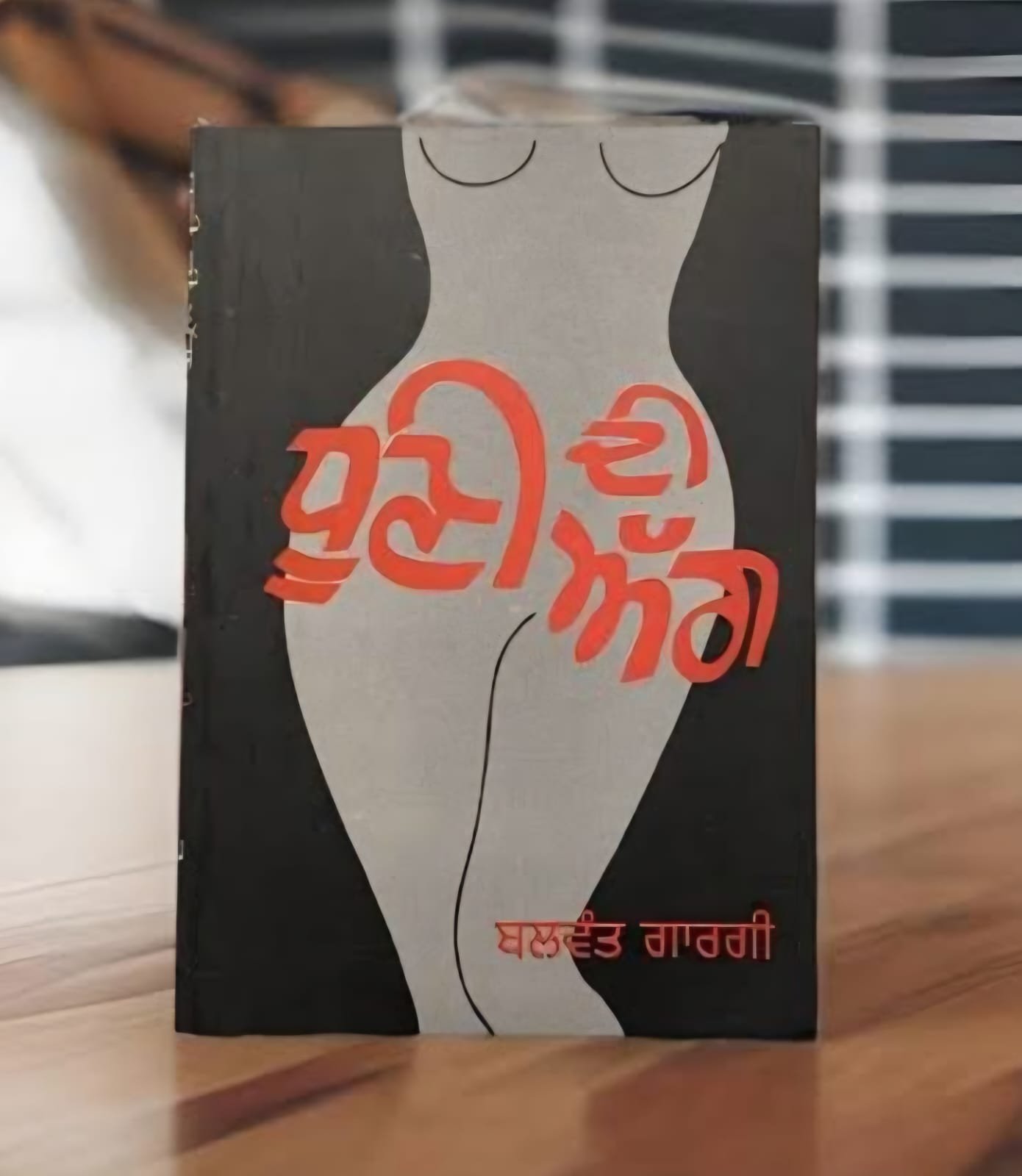

That is what I do. I take what I see and live, mix it with what I imagine, and from that blend, my plays are born. They grow out of the soil I have walked on. I have seen the fog of opium and alcohol settle over the villages of Malwa — it gave me my first play, Eh Jang Kaun Ladde (“Who Will Fight This War”). I have stood beside the homes of small farmers who ended their own lives, and I have felt the quiet despair of Dalit families — from this came Khudkushi de Mod Te (“At the Turning Point of Suicide”) and Bhubbal Di Agg (“The Fire in Ashes”).

I have watched the loneliness of the elderly, and from it emerged Tū Mērā Kī Lagdaĩ (“What Do You Mean to Me?”). I have seen young men, chasing the dream of foreign lands, return in disgrace on deportation flights — their stories took shape as my play Chhalla (Chhalla, a traditional figure of Punjabi culture, who took the boat into the river in place of his father (Jalla) — and was drowned in the waves of the river…

But in these plays, nothing happens exactly as it did in life. The raw moments — scattered, half-formed, chaotic — ferment within me for years. Then, slowly, they find their order, their rhythm, their place on stage. The farmer Bachittar Singh, for example, carries the features of many farmers I have known. His life is stitched from dozens of real lives, but the thread is mine.

That play is perhaps the closest I have come to putting my own life on stage. In it, I have lived — with my family — the same choking struggles of small farmers in my village, their days spent neck-deep in debt and worry. And so, in telling his story, I have told my own.

I have never been able to write about the village without writing about the Dalit community. They are not just a part of its life — they are its pulse, its unacknowledged architects, its unrecorded historians. In my plays, the agrarian crisis and Dalit consciousness have always walked together, hand in hand, because that is how they exist in life itself. The Dalits have built the villages — their homes, their fields, their celebrations — and yet, they have been made to live on the margins. Centuries of caste have forced them to drink humiliation like a slow poison, and even now, their throats burn with it. They are still “those who live outside the village,” still not quite allowed into the bright circle of the mainstream.

I could not ignore this reality in Bhubbal Dī Agg — The Fire in Ashes. That play became my way of holding up a mirror to a society split between caste and class. In the story, the affluent farming caste manipulates the lower farming caste, binding them with the ropes of caste loyalty, while together they look down on the Dalits. The lower caste is closer to the Dalits in poverty, in labor, in the ache of the hands and the hunger of the belly — but caste identity pulls them away. This tangle of “caste versus class” runs through the veins of the play.

What pains me is that the exploitation I wrote about has not disappeared; it has simply changed its clothes. In the era of sharecropping, it wore one face; in the age of daily-wage labor, it wears another. Even now, caste lines slash across love — a boy and girl from different castes cannot marry without risking blood. A famous Punjabi poet Lal Singh Dil expresses the same pain in a poem:

You love me,

but you are of another caste, girl.

Even our dead are not allowed

to burn on the same pyre …”

And today, new divisions are rising: “local Dalit” against “migrant Dalit,” both fighting for their own fragile foothold. Landlessness is still the Dalit’s shadow, and the fight for the legal one-third share of common village land has turned many villages into battlegrounds. Yes, education and jobs have brought some change, but the chasm remains wide, deep, and raw.

Another play of mine grew from a very different wound. Tū̃ Mērā Kī Laggadē̃ — Who Are You to Me? — was born out of watching the quiet suffering of the elderly, left stranded between old loyalties and new realities. It is the tragedy of our times that Indian society has not kept pace with the world it now inhabits. When Europe left feudalism behind, it built systems for the old and the young, safety nets for when the family could not hold them. We, instead, let our ties fray without weaving anything new in their place.

In Tū̃ Mērā Kī Laggadē̃, the story revolves around Pardamman, who dreams for years of a peaceful retirement with his children, only to return to a home where the air no longer feels his own. The gap between him and the younger generation yawns too wide; their worlds no longer touch. Eventually, he leaves, not to chase happiness, but to escape dissonance. His journey is not just his — it is the story of countless elders who have discovered that in this new India, their place at the table is no longer reserved.

The deeper tragedy is not Pardamman’s departure; it is the question his departure leaves behind: How did we lose our elders from our homes? Are the children at fault? The elders? Or is it that our society itself has failed to grow into its new shape? We have not built the systems that could give our elders dignity when families falter. And until we face that truth, the story of Pardamman will keep repeating — on stage, and in life.

There are certain plays in a writer’s life that leave an imprint far deeper than the applause or the reviews. Chhalla is one of mine. It is not just a script bound in pages—it is a part of me, as personal as my own heartbeat. I have carried it from dusty rehearsal halls in Mansa to the grand stages of Glasgow, Scotland. Watching it come alive so far from home was like seeing a child find its own place in the world.

It was my second journey across oceans with a play. The first, Khudkushi De Mor Te (At the Turning Point of Suicide), had already wandered through the cities of America, carrying with it the weight of questions no easy answers could satisfy. But Chhalla—was different. This time, I was chasing a truth that had been troubling me for years: why are so many of Punjab’s young hearts turning their faces to foreign shores? What dreams pull them, and what storms greet them when they arrive?

A playwright is no immigration officer, no politician. I cannot wave a hand and keep someone from leaving; nor can I open the gates of another country. The forces that set entire generations on the road are larger than any single hand or voice. Yet, in the still hours of writing, I found myself drawn again and again to the empty spaces left behind when our youth depart.

I have seen it often: when a society leaves its young without work, without purpose, without a horizon to aim for, the idle hours become a trap. Shadows move in quickly—agents whispering of golden streets overseas, gangs offering a twisted sense of belonging, the ever-present lure of escape. Some leave for the promise of a paycheck, others to flee dangers that have crept too close to home.

In Chhalla, I tried to hold up a mirror to these departures. I wrote of the hopeful, boarding planes with dreams in their eyes, only to find themselves cleaning tables in cramped rooms, bent under debts that bind tighter than any chain. I wrote of those who, chasing a quicker route, are lured into illegal crossings and end up deported in planeloads, their return marked not by garlands but by silence—or worse, by the weight of a coffin. I wrote of the long, weary years some endure before they can finally carve out a place for themselves in lands that were never waiting for them.

I do not fool myself into thinking a play can stop migration. The roots run deeper—into the soil of our politics, our governance, our social will. Unless our governments rid our streets of drugs, break the hold of gangs, restore law and order, and create work that matches the skills and spirit of our youth, the tide will not turn. And across the seas, countries like Canada, Australia, New Zealand, England, and the USA are not beckoning for love of our children—they are filling their own needs. When those needs change, the doors close, the laws tighten, and the same hands that once welcomed begin to push away.

I have come to see that ‘Chhalla’ is not just a name, nor only a character in a play. For me, it has become the face of so many young people I have known—or heard of—who set out chasing dreams, yet never found their way back home.

In Punjab, Chhalla takes many forms.

- I remember first hearing of the folktale, where Chhalla, defying his father Jalla’s wishes, rowed his boat into the stormy river. He was stubborn, reckless perhaps, but full of that restless fire of youth. The river swallowed him whole—boat, passengers, and all.

- Then came 1947. I can still hear the silence in the stories of those who left home with the simple hope of returning. They never did. Thousands of young men, cut down by a Partition that tore through families like a blade through cloth. Their Chhalla was the dream of reaching their soil again—a dream the border never allowed.

- Later, I met another kind of Chhalla: the students. They longed to study one thing, but their parents, heavy with their own unfinished dreams, forced other burdens on their shoulders. I watched some bend under the weight, others break. Some slipped quietly into despair; a few lost themselves to madness.

- And still, the story keeps repeating. I have seen planes full of Chhallas, boys and girls who left for foreign shores, chasing work and survival. Some drowned in unforgiving seas. Some ended up as bonded laborers. Some vanished into prisons far from home. And some returned only as names on a deportation list, their dreams crammed into flights that brought them back empty-handed.

Every time I hear the word Chhalla, I no longer think of just a single boy in a folktale. I see the faces of a generation—faces that keep leaving, and too often, never return.

If we want our Chhallas to stay, we must give them a homeland worth staying for—a place where dreams are not chased across oceans but nurtured under our own skies. Until then, I will keep writing. Not because I believe my words alone can halt the exodus, but because I know the stage can make us see—really see—the tangled web of hopes, deceptions, and harsh truths that lie behind each departure. And perhaps, in the seeing, something in us will begin to change.

From “Black Waters” to White

I have spent my life in classrooms, though my real work was never confined to four walls. As a school teacher, I have always found myself closest to that restless generation standing on the threshold between childhood and youth. Their questions, their hesitations, their dreams — these have been my constant companions.

There is one episode from my personal life as a teacher that I often look back on with a sense of irony. My mother tongue was Punjabi, yet fate had its own design. When Punjab was divided in 1966, my village happened to fall just four hundred meters across the border, into Haryana. That small stretch of land altered the course of my education. I grew up studying in Hindi medium schools, not Punjabi.

It was this accident of geography that set the path for my profession. In Punjab, I was appointed as a Hindi teacher, even though my heart and heritage were steeped in Punjabi. Later, determined to stay close to my roots, I went on to earn a PhD in Punjabi. But life has its peculiar twists—despite my highest degrees being in Punjabi, my teaching remained bound to Hindi.

In time, I pursued an MA in English, and with that came another turn: I was promoted to the post of an English lecturer. So it happened that the very subject in which I had invested my deepest study—Punjabi, my mother tongue—could not shape my career. And yet, it has never stopped shaping me.

As teacher, Most of my years were not spent in the well-lit, well-equipped schools of Punjab’s prosperous towns. Instead, I chose to teach in the region that had been left behind by progress — the kind of place where, as people from the cities would joke, “a man grows old just getting there.”

That place was Mansa district, and beyond it, the dusty borderland touching Haryana. The names of its villages still ring in my ears — Reond Kalan, Boha, Mofar, Jhuneer. To most people, they meant poverty, remoteness, and hardship. Reond Kalan, especially, carried a certain grim reputation. They called it the “Kala Pani” of Punjab — our own “Black Waters” — not because of the sea, but because it was the last village in the district. For decades, if a teacher from Ludhiana, Faridkot, Ferozepur, Hoshiarpur, or Amritsar was transferred as punishment, their destination was Reond Kalan.

It was to this place — this so-called exile — that I gave the golden years of my life. My aim was simple but audacious: to turn “Black Waters” into “White.” And, in time, I believe I did. Today, there are nearly fifteen teachers and government employees from that village. Many were once my students; others, though not formally taught by me, were still touched by the ripples of my work.

But no transformation happens alone. I began by gathering companions who shared my stubborn hope — fellow teachers like Dr. Davinder Boha, Sukhdev Singh Dhaliwal, Dayal Singh, Dr. Paramjit Virdi — and seasoned literary voices like Niranjan Boha, Avtar Khahira, and Principal Harinder Bhullar. Later came my former students, now teachers themselves: Gurnaib Manghaniya, Gulab Singh, Gurdeep Singh, Jatinder Singh, Santokh Sagar, Sagar Surinder, and others. Together, we set out to bring a cultural and literary awakening to these villages.

Our dream took shape in the form of Shaheed Bhagat Singh Kala Manch Punjab. At first, it was just a platform for organising “Art Fairs” — small, spirited gatherings of theatre, poetry, and song. But year by year, those gatherings grew, taking root like a young sapling. Today, that sapling is a twenty-two-year-old tree, counted among Punjab’s major literary and cultural festivals. From its stage have stepped hundreds of theatre artists and countless other performers — singers, debaters, poets, dancers, and musicians — many of whom have won gold medals at the university level and now carry their art to audiences far beyond these fields.

The change has spread beyond the fairs themselves. In the region today stand literary societies, art forums, a girls’ college, the Parkash Kaur Memorial Trust, and even the new Mansa unit of the Progressive Writers’ Association of Punjab — all shaped in some way by the collective effort we began.

For me, the work was never just about events or institutions. It was about lives. It meant offering financial help to a student whose family had nothing. It meant keeping a boy or girl in my own home for two or three years so they could finish school. It meant guiding some towards literature, others towards music or the stage.

Looking back, I see more than a career. I see a journey — from the dusty lanes of a place condemned as “Black Waters” to the proud flowering of a community alive with culture and learning. If I have achieved anything, it is that this once-forgotten corner of Punjab now sings with its own voice.

A Journey in Theatre and Words

A new chapter of my creative life began when I left my village and shifted to Patiala. That move widened my horizons; the arrival of social media widened them even more. The world that had once been confined to my immediate surroundings now opened into an expanse of stages, conversations, and stories that could reach across continents.

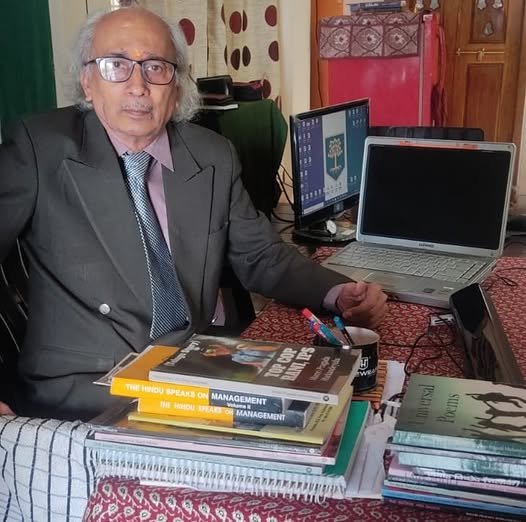

In this new phase, I began experimenting—writing plays with fresh approaches, creating children’s literature, penning narratives, and producing instant, socially-relevant content for online audiences. Criticism, too, became a steady part of my daily labour. My desk was never empty—manuscripts, notes, and theatre scripts piled up beside me, each waiting for its own moment to speak.

I took on roles that bound me even more closely to the literary and theatre world: General Secretary of the Progressive Writers’ Association, Punjab; Convener of the Shaheed Bhagat Singh Kala Manch, Punjab; and the Satish Kumar Verma Research Family. These titles were more than positions—they were responsibilities, commitments to a cultural and intellectual legacy I deeply valued.

The time of Covid opened unexpected doors of possibility for me. In those days of isolation, I found myself more connected than ever. For fifty days in a row, I held fifty online programs through Zoom—each one a gathering of voices refusing to fall silent. On Facebook, I wrote sixty essays in sixty days; words that later took shape as two books, Lockdown Diary, Part One and Part Two. And for the children, shut within the narrow walls of their homes, I carried on for a hundred days without pause, sending out a daily column—little windows of imagination that reached them through the currents of social media.

When the great farmers’ movement of 2020 began to surge, my pen became its witness. Nearly every event of that year-long struggle I tried to capture in words. Across those 365 historic days, I wrote close to 150 essays, pieces that kept spreading, unbidden, across the vast fields of social media. And in that same tide of resistance, under the banner “Poetry in Times of Struggle,” I convened nearly thirty online poetic gatherings, where verse became another form of protest, another way of keeping hope alive.

In those days, Bertolt Brecht’s poem “Motto” (1939) became the slogan of my life:

In the dark times

Will there also be singing?

Yes, there will also be singing.

About the dark times.

After Chhalla, I kept writing. Many of these works are still unpublished—

- Dyer Koi Banda Nahin Hunda

- Main Ajhe Zinda Haan

- Gustakh Auratan, Silsila

- Nalua Sardar

- Suicide Note

- Panjvan Chirag (on third-gender issues)

- Ajhe Vi Waqt Hai (on the mother tongue Punjabi, the only full-length play of its kind).

At present, I am preparing a five-volume set of plays for children, grouped by age.

One of the works closest to my heart from this period is Main Jallianwala Bagh Bolda Haan (I am Jallianwala Bagh, and I speak). It was an experiment—a “Nano play series” for children—and it was honoured with the Sahitya Akademi’s 2024 Bal Sahitya Puraskar. Nano-Theatre is a bold new stream in Punjabi drama—perhaps the smallest dramatic form our stage has ever known. In it, a single heartbeat of life, a fleeting moment, or the echo of an everyday encounter becomes theatre. Nothing is too brief to carry meaning; nothing too small to hold the weight of truth.

It is not a monologue, nor merely a short play, nor just a skit. It is its own current, its own voice. And I carry a certain pride in declaring that this current first broke ground with my play “I Am Jallianwala Bagh, Speaking.” From that cry of history was born a new way of telling—compressed, piercing, unforgettable.

Nano-Theatre is not just a form; it is a movement. A reminder that even the tiniest spark can set fire to the stage, that even the smallest fragment of life can mirror the vastness of our collective struggle and memory.

By now, thirty-three books bear my name. They span opera collections, full-length plays, children’s narratives, research studies, criticism, editing projects, translations, poetry compilations, memoirs, and thematic anthologies. Each book is a milestone, but together they form the road I have walked for decades. The complete list of these books is as follows :

- Ih Jang Kaun Lare (Opera collection)

- Khudkushi De Mor Te (Full-length play)

- Tuun Mera Ki Lagdaen (Full-length play)

- Bhubbal Di Agg (Full-length play)

- Chhalla (Full-length play)

- Main Jallianwala Bagh Bolda Haan (Nano play series)

- Vishav Opera: Siddhant, Saroop ate Sarokar (Research)

- Bharat Di Sangeet Nataki Parampara (Research)

- Natak Te Rangmanch: Aadhaar Te Pasaar (Criticism)

- Punjabi Natak Te Rangmanch: Adhiyan Te Alochna (Criticism)

- Punjabi Nataki Paathan Da Paathgat Adhiyan (Criticism)

- Punjabi Mini Kahani: Paath Te Prasang (Criticism)

- Laghu Katha: Siddhant Te Vihaar (Criticism)

- Mall Singh Rampuri De Operay: Paath Pariprekh Te Pardchol (Editing & Criticism)

- Jelhan Jai: Paath, Pariprekh Te Pardchol (Criticism)

- Bhullia Visaria Kavishar: Jangeer Singh Brar (Editing)

- Qaumi Shaheed Bhagat Singh (Editing)

- Aurat Tere Roop Anek (Editing)

- Manikvachakar (Translation from Hindi)

- Lockdown Diary–1 (Narrative)

- Lockdown Diary–2 (Narrative)

- Aa Jao Nikkio Gallan Kariye–1 (Children’s narrative)

- Aa Jao Nikkio Gallan Kariye–2 (Children’s narrative)

- Aa Jao Nikkio Gallan Kariye–3 (Children’s narrative)

- Shabad Shabad Nanak (Poetry editing)

- Asin Sirf Bacche Nahin Haan (Children’s poetry editing)

- Prism Vicho Disda Satish Kumar Verma (Editing of sketches)

- Aadhunik Manukh Di Laghuttmi Hond Da Pravachan: Kamriyan De Bahar Baitha Ghar (Review editing)

- Mere Hisse Da Aulakh (Editing of memoirs)

- Face to Face (Narrative)

- 2021 Da Punjabi Nat-Munch (Editing)

- 2022 Da Punjabi Nat-Munch (Editing)

- 2023 Da Punjabi Nat-Munch (Editing)

When I look back, I see myself holding the branch of Punjabi drama’s fourth generation and now riding the carriage of its fifth. The fourth began long before me; the fifth is only just finding its voice. At the dawn of the twenty-first century, I felt the winds shifting and knew that a new generation of theatre was possible. If that vision takes shape, perhaps my own work will be one of its possibilities.

In the fourth generation, names like Dr. Satish Kumar Verma, Swarajbir, Pali Bhupinder Singh, and Dr. Davinder Singh stood tall. My own journey began quietly with Ih Jang Kaun Lare, a collection of operas. From there, I staged and wrote plays across Malwa, filling evenings with rehearsal-room debates and the smell of fresh paint on wooden sets.

Fifteen full-length plays, around ten one-act or short plays, two nano plays, and some thirty children’s plays now bear my signature. Six of the children’s plays are already in print; the rest wait patiently in my files. These works have travelled—performed in India and abroad, studied in MPhil dissertations, examined in PhD research, and included in university syllabi.

Four of my books are devoted entirely to theatre criticism. But beyond numbers, titles, and lists, what matters most is this: for more than twenty-five years, I have worked with diligence and passion in the worlds of drama and theatre. I cannot say whether I am ahead or behind anyone. What I can say is that I am deeply satisfied—because I have lived my life in the service of the stage, and in return, the stage has kept my spirit alive.

Agriculture & Industry

Applied Arts

Biographical Writings

Career & Skill Development

Children Books

Computers & Information Technology

Myths, Culture & Folklore

Economy & Finance

Education & Exams

Fine Arts

General Knowledge & Reference

Health & Wellness

History

Language & Linguistic Studies

Law & Criminology

Literature & Literary Studies

Media & Journalism

Medical Sciences

Motivation & Self Help

Performing Arts

Philosophy & Ideology

Politics & Political Science

Public Administration

Religion & Spirituality

Science & Engineering

Society & Social Sciences

Sports, Travel & Hobbies

India: National & State Concerns